In ,part one of this post, I shared some background on Dr. Stan Tatkin’s Ten Commandments for creating secure-functioning relationships. Essentially Tatkin wrote ten guidelines for having our best, healthiest, most mutual relationships, using old English vernacular that, in my opinion, could do with an update — an update that honors the powerful language and essence of these pointers, but is easier to digest. In the first post, I provided rules one through five, with a little unpacking for each.

In this post, I will continue with the final five, as well as provide some practical tips and tricks for remembering and enacting these guidelines to build more safety, love, and security into your relationship. Let’s dig in.

6. Protect your partner in public and in private from harmful elements, including yourself.

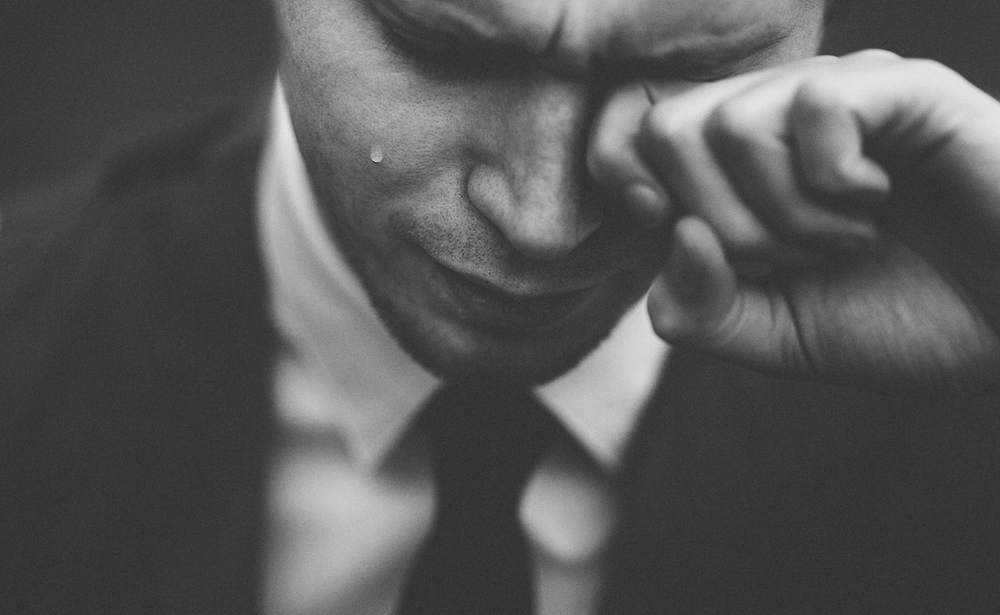

This one can be a tear-jerker in the most heart-warming sense. Who does not love to be protected? Can you remember a time when someone stuck up for you in public or pulled you back from mindlessly crossing a busy street? Anytime someone protects you from something physically, emotionally, or psychologically harmful, there is something tender and precious about it, right? One reason for that is because it speaks to our inner child and all the ways we may not have been protected in the past.

One of my somatic therapy mentors uses a technique that has helped me grasp this in a poignant way. Those of you who have done good therapy are aware that we often go through a healthy form of psychological regression in a powerful session, feeling smaller or younger than we actually are.

As we work with certain issues or feeling-states, we may find ourselves shrinking our posture, lowering our voice, or otherwise experiencing a much younger state of mind. When this happens with her clients, my mentor emphasizes the need for implanting a felt-sense of protection. She says, “Every traumatic event that occurred during childhood comes with the additional trauma of not being protected.” Nothing that happens to a four-year-old is their fault. Every child has the right to expect a reasonable amount of protection from harmful elements.

And you have the right to expect the same in your romantic relationship. No other relational space is as intimate, vulnerable, and potentially dangerous as childhood, but our adult romantic relationships are a close contender. And everyone willing to brave romantic — to be so vulnerable — deserves protection.

So, step up and help during a situation you know is inherently challenging for your partner, watch for and intervene during moments in public that are reminiscent of your partners’ relational wounds, gently remind them of self-care when they resort to destructive behaviors (such as addiction or overeating), silence yourself before speaking to them harshly, and watch for all the ways you can protect your partner — your greatest asset.

7. Put your partner to bed each night and awaken with your partner each morning.

The heartthrobs continue. Can you remember the last time someone put you to bed? Perhaps with a song, a story, or merely a kind verbal send-off? For many of us, we were much younger when this last happened . . . noticing a theme yet?

According to the Center for Disease Control, ,70 million Americans¹ struggle with chronic sleep problems, and nearly one third report regularly not getting enough sleep. While we may not stop to think about it too often, there are many elements of going to sleep that are challenging for a lot of us.

First of all, sleep typically ,requires us to access the parasympathetic function² of our autonomic nervous system — essentially the brake to our physiology, which helps us calm down, relax, rest, and digest. This can be a major issue for people with trauma, as trauma often disables this function for the sake of hypervigilance, causing the relaxed state associated with the parasympathetic branch to be interpreted by our nervous system as dangerous. This is usually a subtle phenomenon. We typically do not notice the fear, but rather find ourselves slightly restless as bedtime approaches and quickly reaching for something to distract us from our immediate experience, such as a drink, TV show, or spiritual practice.

From a more psychoanalytic perspective, sleep is the time when the veils between our conscious and unconscious mind are thinnest. While our unconscious mind is the seat of our healing, it often contains a lot of challenging material (including traumatic memories), which we spend oodles of effort attempting to avoid. So in a similarly subtle fashion as the fear we may experience in our nervous system, it can be unnerving to willingly cross the threshold into dreamscapes, memories, and uncontrollable emotions that can emerge during dreams.

Relationally, bedtime can be a notoriously lonely hour. In a busy and social world with all sorts of sensory input, many of us do not have an abundance of time alone with our minds. If our day has been full of interactions, tasks, and actions, it can be jarring and unsettling to have to face the aloneness that comes with a pitch dark room and no sounds save our own thoughts, which suddenly seem loud and fast.

When children experience the stress associated with this (and they usually do), they typically have little problem asking for comfort. Stan Tatkin’s Relationship Rule #6 is a reinstatement of that wonderfully childlike piece of wisdom: face the fear and vulnerability associated with sleep by eliciting the support of those closest to you.

You can read to each other, have gentle pillow-talk, or simply make a habit to be in the bed at the same time and wish each other a pleasant night of sleep. When we pay attention to and become accustomed to this kind of support, it can go a long way.

8. Correct all errors, including injustices and injuries, at once or as soon as possible, and do not dispute who was the original perpetrator.

This rule is all about memory.

While at first glance, the idea of correcting relationship injuries quickly while not addressing who threw the first punch might sound conflict-avoidant and pollyannaish, we are actually talking about a different level of relational functioning here — one heavily backed by neurological research on memory.

Experiencing and then correcting injustices and injuries in relationship is often called rupture and repair by couples therapists, and this process is considered essential to building a strong bond. We need to know that our sense of connection can handle bumps in the road and endure. But just how much rupture is ideal and how quickly should we repair it?

Memory is a ,far more dynamic and elusive function³ than we often give it credit for. Memory formation occurs over time: short-term, to recent long-term, to remote. This over-time occurrence influences the type of memory we are encoding: declarative (shopping-list memory), emotional (as it sounds), procedural (riding a bike or trauma stored in the body), flashbulb (startle responses stored in the amygdala), and narrative (a combination of all the above overlaid onto our sense of self).

These complex factors create a myriad of potentialities when it comes to the way we remember an event and the accuracy of the details we recall. Fortunately (for all of us in relationships), you do not have to understand these complexities in their entirety to know the most relationally beneficial way of approaching rupture and repair.

The two factors we need to know about memory to improve our relationships are: 1. Our memory of relationally disruptive moments is faulty and 2. We want to prevent creation of long-term memories associated with relational ruptures.

,There is research⁴ (and a lot of anecdotal experience) suggesting that when we fight with our partner or have even begun to feel a subtle level of abandonment, rejection, or neglect in our relationship, our hippocampus (the part of our brain that heavily contributes to the accuracy of declarative memory) struggles to function properly. This means the more relationally stressed we are, the more we will remember the emotional experience, but the less we will remember the concrete details of what happened. This loss of detail is also positively correlated with the length of time we are stressed. The longer we fight, the less accurate our memory becomes.

This memory loss is largely due overactivation of threat responses in our nervous systems. Just under the surface of every relational dispute is the possibility of losing our partner — a major threat to our well-being.

This sense of threat colors our perception of the moment and we tend to see more of our past and all the previous relational threats to our well-being than we see of the current situation. This is why there is no need (especially during the fight) to discuss who started it. In all likelihood, the original perpetrator of your current feelings was someone from much earlier in your life, and when it comes to the current dispute between you and your partner, you will not remember who was the original offender accurately, anyway. Also, knowing who started the dispute is not relevant to the immediately important task of initiating repair.

Why is the task of beginning repair such an urgent need? The longer we remain in a state of rupture and the more repetitive punches we throw, the more we create long-term memory associated with insecure attachment and disconnection. This type of memory creation ,rewires our brains⁵ to suspect it in the future, look for any sign of it in the present, and latch on to it as the status quo. Our brains are biologically wired to look for danger (like the danger of losing the ones we love) over security. We do not need to help it along by remaining in tumultuous rupture any longer than necessary.

The possibility of creating long-term memory during disputes and injuries is strengthened or decreased by how well you mediate time, repetition, and sleep.

When it comes to time, you should stop combative behavior or language and begin building repair as early as possible — no longer than 20 minutes is a good, if challenging, rule of thumb. Second, watch for repetitive slights within a single fight, or over the course of time, and make an agreement that all talking ceases if they begin. Lastly, always resolve issues before you sleep, as ,this is the time⁶ the hippocampus largely converses with the frontal cortex to create lasting memories.

How do you move to repair in these challenging moments? Dr. Tatkin says, “Secure adult romantic partners tend to defuse (not dismiss) negative moments through mutual attenuation of painful affects.”³ In other words, stop arguing over details and redirect your attention to the painful emotions you and your partner are feeling.

Attuning to emotions opens your heart to the fact that the pain driven by the rupture is far more important than who was responsible for the broken cellphone screen or missed appointment. This realization naturally drives us back to repair, where we can continue to empathize and understand one another. If interrupting these cycles seems impossible, seek out a good couples therapist.

9. Gaze lovingly at your partner daily and make frequent meaningful gestures of appreciation, admiration, and gratitude.

Your partner is the most important person in the world. So let them know that and let them know why — duh! We can do this very well with words of appreciation, admiration, and gratitude. But, in my opinion, the loving gaze is a special method.

Dr. Diane Poole Heller, adult attachment expert, calls this the gleam beam: looking at your partner with love in your eyes and expressive facial features.

There is a famous study initially conducted with infants by Dr. Edward Tronik, director of the Child Development Unit at Harvard University, called the ,still-faced experiment.⁷ In these heartstring-pulling studies, mothers coo and make all sorts of loving and playful faces with their baby. The babies predictably respond by contorting their own faces to participate in a dynamic interplay of joint emotional states (called mutual contingency).

In the experiment, once this interplay has begun, the mother then drops all expression and assumes a still face for two minutes. Securely attached babies will attempt to use all methods at their disposal to get the mother’s active expression back. When this fails, they become extremely distressed. The mutual contingency inherent in facial interaction is vital to the baby’s growing ability to regulate their own emotions, understand nonverbal communication, and develop healthy bonds. Children’s distressed reaction to the still face has been found to be a ,strong predictor of secure attachment.⁸

Giving loving, emotional gazes to out partner gets right to the core of interactive regulation — the ability to calm our nervous systems, regulate distress, and access safety via engagement with a loving other. It is also cute as hell.

10. Learn your partner well and master the ways of seduction, influence, and persuasion, without the use of fear or threat.

This rule is a reminder that being entrusted with your partner’s love, affection, and dedication requires and deserves work. Remember, they deserve your care and their happiness is yours. Becoming an expert on your partner is a must.

In my couples therapy, I often use a technique called cross-questioning to facilitate partners in this process. I will look at one partner and ask them, “Why is your partner sad right now and what do you know about their history that warrants sadness in this situation?” You have to know your partner this well, and much more. Ask them all about their early childhood, love languages,⁹ diet and health issues, etc. The more you know, the better you can take care of them and the better they can then take care of you.

In this rule, Dr. Tatkin highlights mastering your ability to seduce, influence, and persuade. Seduction can mean influencing your partner to want to come closer to you or to do something you’d enjoy together, but most often we use this word in the context of sex. Sex is monumental to secure connection and it almost goes without saying that laziness simply will not do here. You have to put in the effort to get to know them and what turns them on.

Mastering influence and persuasion is a bit more tricky to understand. Tatkin is not referring to anything manipulative. Rather, he is speaking about knowing your partner’s soft spots. Learn what is important to them so you can to bargain and persuade them to go on the road trip they are apprehensive about, but that will satisfy you deeply, improving your ability to love and care for them. This is influence and persuasion.

Know the sort of food that lifts their mood, the sort of activities that help them come down after a hard workday, and the sort of touch that helps them return to their bodies. This is influence in the most transformational sense. You can influence your partner to quickly decompress and destress in the short term, find joy instead, and even aid in healing long-term mental illness. Don’t be scared to be this important to your partner — they deserve better than your fear. They deserve your action. So long as both partners are committed to being such an expert and mastering heartfelt influence, you cannot fail each other.

Mastering the Art of Secure Attachment: Tying it All Together

Now that you know the importance of protecting your partner and putting them to bed each night, how to move through rupture and repair, the significance of loving glances, and why you need partner-specific expertise, how do you enact all of these ideas? How do you keep up with so much romantic improvement amongst jobs, children, creative pursuits, and life’s stressors? Let me offer a few simple but important points.

First, read Stan Tatkin’s ,Wired for Love and Diane Poole Heller’s ,The Power of Attachment. And read them together with your partner. They are full of poignant information and helpful exercises you and your partner can do to drive these points home and work to dislodge any blocks to enacting these rules.

Second, be patient and tackle the rules one at a time. I often recommend that my partners buy sticky notes, write the rule they are currently working on on several of them and place them around the house and in the car. This might seem simplistic, but you may have a lifetime of neural connections and habits built and designed to keep you from secure-functioning relationships. Patience and constant reminders can go a long way. In addition, you can check in with each other each night before you go to bed (together, of course) on how you did that day.

Lastly, if your partner protests and outright rejects one or some of these rules . . . I’d consider getting out of that relationship. But if both partners are willing to work and desire secure functioning, but one or both of you struggle to enact these practices, see a skilled couples therapist. Your relationship is worth it, and much more.

Relationship Advice References

- CDC – about our program – sleep and sleep disorders. (2017, June 05). Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- Fink, A. M., Bronas, U. G., & Calik, M. W. (2018). Autonomic regulation during sleep and wakefulness: A review with implications for defining the pathophysiology of neurological disorders. Clinical Autonomic Research, 28(6), 509-518. doi:10.1007/s10286-018-0560-9

- Solomon, M., & Tatkin, S. (2011). ,Love and war in intimate relationships: Connection, disconnection, and mutual regulation in couple therapy (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). W. W. Norton.

- Wolf OT. HPA axis and memory. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003 Jun;17(2):287-99. doi: 10.1016/s1521-690x(02)00101-x. PMID: 12787553.

- How memories are made: Stages of memory formation. (n.d.). Lesley University | Lesley University.

- Axmacher N, Elger CE, Fell J. Ripples in the medial temporal lobe are relevant for human memory consolidation. Brain. 2008 Jul;131(Pt 7):1806-17. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn103. Epub 2008 May 24. PMID: 18503077.

- Still Face Experiment clip, Dr. Edward Tronick.

- Cohn, J., Campbell, S., & Ross, S. (1991). Infant response in the still-face paradigm at 6 months predicts avoidant and secure attachment at 12 months. Development and Psychopathology, 3(4), 367-376. doi:10.1017/S0954579400007574

- Mostova, O., Stolarski, M., & Matthews, G. (2022). ,I love the way you love me: Responding to partner’s love language preferences boosts satisfaction in romantic heterosexual couples. PLOS ONE, 17(6), e0269429.