In a recent conversation, my mom asked me why some people become addicted to drugs while others do not. I love when conversations go in a challenging direction. I got to thinking about it, and I wanted to put forth a few ideas. However, albeit an interesting topic, I want to relieve you of any possible suspense: we do not really know the answer to this, yet. There has been no empirical, quantifiable proof discovered. Addiction professionals are still debating, each in their own way.

Materialists have been trying to link deficits of certain neurotransmitter receptors or low amounts of gray matter to the probability of addiction (Ersche, et al, 2013 & Benton and Young, 2016). Some are genetically modifying mouse endocannabinoid receptors to isolate their impact on the cause of addiction (Maldonado et al, 2013). Many are still debating the disease model, while some continue to pursue behavioral implications. Unfortunately, none of these are bringing us terribly close to an answer.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Fortunately, there are some who have stumbled upon an outlook that goes beyond neurology and genetics. Many of us have heard about Vincent Felitti and his Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACES). For those who have not, Dr. Felitti was the chief of Kaiser Permanente’s Department of Preventative Medicine in 1995. Inspired by his work with obese clients struggling with eating disorders, Felitti decided to compose a survey assessing the frequency of traumatic childhood experiences.

The survey was then given to 17,421 people—mostly white, middle-class, middle-aged, well-educated, and financially secure individuals. They were surveyed for ten different kinds of adverse experiences in their childhoods. Surprisingly, only one third reported having no childhood traumatic events.

Felliti laid this information over each person’s medical record to look for patterns. Suffice it to say that the more adverse childhood experiences reported, the higher the likelihood of troubling medical and psychological conditions. And the statistics culminating in this likelihood were staggering. When it came to addiction, the results were just as alarming. (For a full review of the ACES literature)

People who reported four or more adverse childhood experiences were seven times more likely to be an alcoholic. For every adverse experience, the likelihood of early initiation of drug use increased two to four fold. And for those with a score of six or higher, the likelihood of intravenous drug use was 4,600% greater. 4,600%. Let that sink in.

Gabor Mate

Felitti is not the only doctor linking trauma to addiction. Public speaking sensation Gabor Mate has been changing the dialogue around addiction for many years now. This began after he observed that nearly every woman he treated in his Portland, Oregon facility for intravenous drug use had been sexually molested as a child (Mate, 2008). Mate, along with many others, are attempting to rewrite the common knowledge on addiction by addressing its traumatic, physiological underpinnings.

Trauma and Addiction

To understand the link between trauma and addiction, we need to understand trauma. Trauma is often misunderstood to be an overwhelming event, but trauma is actually, when the physiological impact of an event becomes chronic. This distinction is crucial.

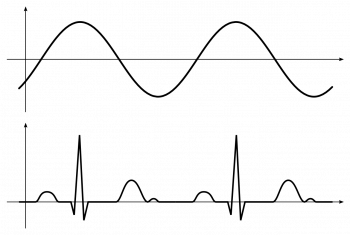

Physiologically, we are designed to live within a certain level of autonomic nervous system activation. In a nutshell, this part of our nervous system oscillates up and down throughout the day. When we get up in the morning, our sympathetic (excitatory) nervous system activates and prepares us to walk to the bathroom. When we let out that relieving urine and our shoulders drop in relaxation, our parasympathetic (inhibitory) nervous system kicks in to settle us. We go to the kitchen to cook breakfast—sympathetic—we sit at the table to digest it—parasympathetic. We become alertly mobile while driving to work—sympa; we relax at a friendly coworker’s welcome—para. All day long.

Window of Tolerance

When enduring a traumatic event, we break out of this healthy oscillation. Our survival system—embedded within this same autonomic system—goes into hyperdrive or gives out altogether in preparation for defeat. Even this is not necessarily a problem, yet. We are designed to handle large amounts of stress and rebound. However, this rebounding only comes when we are able to take corrective action, or have others take it for us (Levine, 1997). When this does not happen, our nervous system activation, or total collapse, becomes stuck outside this level of healthy oscillation, known as the window of tolerance (Siegel, 2009).

The window of tolerance is a very subtle topic that has (unfortunately) been diminished to jargon in many circles. Because of its subtlety, it is beyond the scope of this post to cover it in full detail. For our purposes, it will suffice to say that while the experience of the window of tolerance is highly personal, the window has a universal physiological basis—all humans are operating with the same nervous system structure.

I like to imagine the window of tolerance as a range in our nervous system that, when we go above or below it, we get dysregulated. Going above the window (hyper-sympathetic state) could look like racing thoughts, anxiety, increased heart rate, shallow breathing, hypervigilance, and panic attack. Going below the window (parasympathetic freeze) could look like dissociation, physical numbness, constricted muscles, and an extreme lack of social engagement (Chitty & Castellino, 2014).

Trauma pushes us outside our window of tolerance: our nervous system reacts to threat, this reaction causes a defensive response that was thwarted, our nervous system remains defensive. Remaining defensive, we are now hardwired to expect danger around every symbolic corner. For example, with my core trauma being relational, I can view relationships themselves as threatening, and they can therefore, push me outside of my healthy window. And living outside of our window of tolerance leads to serious long-term symptoms. (Not all traumatic events need be severe to cause dysregulation)

When we are autonomically operating outside of our window of tolerance for extended periods of time, we have less access to choice, reason, and intuition. Our emotions become can become volatile or inaccessible. We may develop high blood pressure, digestive problems, and autoimmune disorders. The list goes on and on. But most importantly, it is psychologically painful.

In alignment with the long history of depth psychology, I believe the unconscious contents of our minds want to become conscious. Dysregulation is the way we keep overwhelming internal experiences buried. As F.M. Alexander, an Australian actor who developed a technique to overcome habitual postures and movement, said, “When psychologists speak of the unconscious, it is the body that they are talking about.”

While living dysregulated, we desperately want to return to a state of healthy activation. But when we have no one around to point out our dysregulated cycle, and teach us how to rebalance, we look for any way we can to live more tolerably within our dysregulation.

Cue addiction. On the lower end of severe autonomic imbalance, those of us living outside our window of tolerance have responsibilities to meet and relationships to keep intact. These ordinary life tasks can become severely challenging when concurrently dealing with a baseline level of nervous system dysfunction within our very skin. On the more severe end of the spectrum, we may be so far outside our window that we do not want to live at all. In both cases, with no genuine access to our actual window of tolerance, we create a faux window (Kain & Terrell, 2018).

Faux Window of Tolerance

The faux window of tolerance is the artificial replacement for genuine regulation. It is one more example of the intelligence we humans display in survival situations. When I could not figure out how to regulate through relationship—because I viewed them as so threatening—I turned to drugs. Unfortunately, the actual survival situation which caused our dysregulation has often become obsolete, replaced by years of turmoil, anxiety, and depression, which our faux window, bent on homeostasis and keeping the status quo, perpetuates.

Sometimes, we can even tell whether the addict’s nervous system is over-charged or over-inhibited by which drugs they use. If someone lives with unchecked, lethargic freeze, they may prefer stimulants as a substitute for the missing charge. And if someone lives with high anxiety and restlessness, they may prefer benzodiazepines or be a heavy drinker to give themselves the impression of groundedness. Unfortunately, this pattern is not universal—stay tuned for future articles.

Why Drugs?

So, mom, why do some of us become addicted to drugs when others do not? Looking with regulation-oriented eyes, there are two possible contributing factors. First, those who are mostly regulated do not need artificial means to bring their nervous system into balance. Therefore, when they have a drink with dinner, their mind does not obsess (as mine certainly did) about stopping at the liquor store on the way home. They enjoy a drink, and have some tea with dessert.

Those of us who cannot find our real window of tolerance will keep trying to get ourselves there, sometimes at the expense of everything else.

It should be added that many people struggle with dysregulation who do not smoke weed every day or need three cups of coffee to function or have other types of chemical dependencies. Often, these people create a faux window of tolerance through non-chemical means. They keep troublesome material locked in the unconscious, avoiding the felt-sense of dysregulation through such tactics as dissociation, projection, denial, or sublimation.

While addiction is certainly a common way we create a livable window, it is not the only one. These other methods can be extremely efficient. Dissociated people can live most of their life with very little awareness of their internal bodily cues, which are signaling danger through dysregulation. Unfortunately, they also lose access to the bodily cues signaling joy, pleasure, and intuition.

People who use sublimation—workaholics and busy-bodies often fit this category—may never realize how much anger is driving their system because they constantly convert that nervous system charge into socially acceptable achievement or activity.

Those who have other means for living with chronic dysregulation may not respond to drugs the same way as an addict because they have the task of creating a faux window covered. So these people, like those who are mostly regulated, might not become addicted to drugs either.

Sobriety

When viewing addiction through this lens, the path to sobriety and sanity looks more like regulation work, and less like abstinence alone. Still, abstinence is quite important. It gives us a chance to sense our dysregulation (and regulation) accurately. But, going beyond abstinence has led myself, and many other addicts to understand that overcoming the impulse of addiction is more than use or not use.

It entails building awareness of our autonomic nervous system—both conceptually and experientially. Unearth what drives the dysregulation, find reparative experience, and regulate. As my Somatic Experiencing teacher says, “Often, we remove the dysregulation and find that the addiction is no longer there.”

Learn more about somatic therapy.

—————————————————————————————————–